Democratic Republic of Congo

Malaria Facts

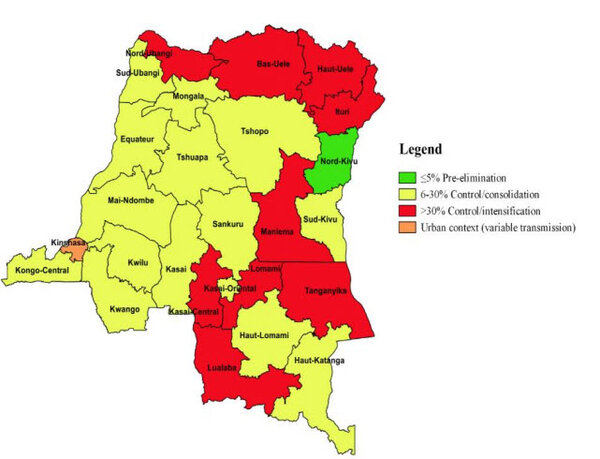

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has the second highest number of malaria cases and deaths globally. In 2021, 12.3 percent of malaria cases and deaths, and 12.6 percent of malaria deaths occurred in the DRC, and the country accounted for 53 percent of malaria cases in Central Africa in the same year. [1] Malaria is among the principal causes of morbidity and mortality in the DRC, accounting for 44 percent of all outpatient visits and for 22 percent of deaths in 2018. [2] Approximately 97 percent of the population lives in zones with stable malaria transmission lasting 8–12 months per year. The highest levels of transmission occur in zones situated in the north and centre of the country. [2] Between 2020 and 2021, the malaria case burden fell by 1.8 percent from 324 to 318 per 1000 of the population at risk. Death rates fell by 3 percent, from 0.85 to 0.82 per 1000 of the population at risk. [1] DRC launched the High Burden High Impact initiative in November 2019 to align interventions with malaria burden for the ten most affected provinces. [2]

Malaria is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in DRC. The greatest burden of malaria morbidity and mortality falls on pregnant women and children under five years of age. 97 percent of the population lives in equatorial and tropical areas, while 3 percent live in mountainous areas, where malaria is unstable.

Further south, malaria transmission is seasonal. This region records 80 percent of its rainfall over four months. The highest levels of transmission occur in zones situated in the north and center of the country. Approximately 97 percent of the population lives in zones with stable malaria transmission lasting 8 to 12 months per year. Access to care in DRC, particularly malaria services, remains a challenge.

As of 2021, the main malaria vectors in DRC are An. gambiae s.l. and An. funestus. These vector species bite both indoors and outdoors with peak biting period between 11:00 p.m. and 3:00 a.m. for An. gambiae s.l, and An. funestus between 6:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m. indoors and 7:00 p.m. to 8:00 p.m. outdoors for An. Paludis.

Nationwide, it’s estimated that only 30 percent of the population lives within five kilometers of the nearest health facility. As a result, the response has been to focus on establishing community care sites (CCSs) with the goal of closing the gap in malaria service provision.

Another challenge is the insufficient number of health care providers at the community and health facility levels; this is especially true in rural areas. Moreover, challenges related to the availability of antimalarials and the functionality of the DRC supply chain system remain barriers to treatment.

The quality of data collected from health facilities and reported into the District Health Information Software 2 (DHIS2) and the Logistics Management Information System (LMIS) is improving, but remains a challenge.

Malaria in young children and pregnant women

In 2016, 13.4% of deaths among children under five years of age in 2016 were because of malaria. [3] In 2016, about 47% of malaria episodes occurred in children under five years of age. [2] Severe malaria is responsible for 77% of hospitalisation for children under five years of age, and 55% of hospitalisation for patients over five years of age. [2] The National Guide for Implementation of Community Care Sites (2016) defines the package of services to include referral of severe malaria cases and treatment of uncomplicated malaria cases in children under five years of age. [2]

In 2017–2018, just over 51% of children under five years of age and 52% of pregnant women reported sleeping under an insecticide-treated net (ITN) the night before. In households with at least one ITN, those percentages increase to 84% of children and 91% of pregnant women – given access, use of ITNs is high.

The National Malaria Chemoprevention Therapy guidelines recommend that SP-based IPTp be given to all pregnant women during ANC visits from the start of the second trimester of pregnancy. Each woman should receive at least four doses of SP during pregnancy. Doses should be administered one month apart until delivery as directly observed treatment at health facilities. Pregnant women are also given an ITN at their first ANC visit.

Household survey data showed improvements in the number of pregnant women who received at least one dose or two doses of intermittent preventive treatment (IPTp): more than 50% of pregnant women received IPTp1 (first dose of IPTp) and approximately 30% received IPTp2 (second dose of IPTp) according to the 2017–18 Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey. The proportion of women who received three or more doses of intermittent preventive treatment – were below 15%. [2]

Severe malaria case management

For pre-referral treatment of severe malaria, rectal artesunate is recommended, or injectable artesunate intramuscularly if the rectal route cannot be used. After pre-referral treatment, the patient should be directed immediately to a health facility with the appropriate equipment to continue treatment.

According to national guidelines, malaria tests and drugs are free for all age groups in DRC. Case management of malaria using confirmatory diagnostic testing with RDTs or microscopy and treatment with ACTs: artesunate-amodiaquine (ASAQ) or artemether-lumefantrine (AL) and the introduction of artesunate-pyronaridine (AS-PYR) for uncomplicated cases and injectable artesunate as the treatment for severe malaria cases. The strategy also includes rectal artesunate for pre-referral intervention at community health centers and at first-level health centers.

Injectable artesunate is the recommended treatment for severe malaria in adults, children over two months of age, and pregnant women in their second and third trimesters. Injectable artesunate should be administered for at least 24 hours and until the patient can tolerate oral medication. Injectable treatment should be followed by an artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) – artesunate-amodiaquine (ASAQ), artemether-lumefantrine (AL), or pyronaridine-artesunate (PA) – at the recommended doses for 3 days. Artemether (intramuscular) or quinine infusion may be used if injectable artesunate is not available.

For infants under two months of age with severe malaria, quinine infusion is recommended, followed by quinine drops to reach seven days of treatment in the country. For pregnant women in their first trimester with severe malaria, quinine infusion followed by quinine tablets combined with clindamycin hydrochloride capsule for seven days is recommended. This however deviates from the global WHO treatment guidelines which state that injectable artesunate is the first choice in this group.

Health Policies

Key updates within DRC’s health policies include the incorporation of World Health Organization’s current antenatal care recommendations into national policies and the Malaria in Pregnancy Strategy. This decision was jointly taken by the National Reproduction Health Program and the National Malaria Control Programme. [2]

Healthcare Facilities

Nationwide it is estimated that only 30% of the population live within five kilometres of the nearest health facility. As a result, the response has been to focus on establishing community care sites to close this gap in malaria service provision. In all of DRC, an estimated 18,350 community care sites are needed for full scale up. Currently, only about 38 percent of these sites (6,968 sites) have been established. [2]

The health system in the DRC has three levels: central, intermediate and peripheral. Towards the end of 2015, the DRC went through a reform to subdivide the country’s previously 11 provinces into 26 new provinces. Many of the new provinces are trying to build up their health centres and systems.[2]

At the community level, there are two types of volunteer health workers: community health promoters and community treatment workers.[2] One community health worker (CHW) is responsible for providing diagnosis, treatment, and referral services while the other focuses on health promotion, communication, and community mobilisation. CHWs are unpaid. Both CHWs are to be trained approximately every two to three years in malaria, pneumonia, and diarrhoea diagnosis and treatment; this includes administration of RDTs, ACTs, and rectal artesunate for severe cases.

Severe malaria policy and practice

| Recommendation | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Strong | Injectable artesunate |

| Alternative | Injectable quinine |

| Recommendation | Pre-referral |

|---|---|

| Strong | Rectal artesunate |

| Recommendation during pregnancy |

|---|

| Intravenous quinine |

Market information