Mali

Malaria facts

Malaria is the primary cause of morbidity and mortality in Mali. Globally, Mali is among the ten countries with the highest number of malaria cases and deaths: 3.1% of the global cases and 3.3% of global deaths due to malaria in 2021. It accounts for 6% of cases in West Africa. From 2020 to 2021, cases fell 1%, from 357 to 354 per 1000 of the population at risk, but deaths increased 6.5% from 0.97 to 0.91 per 1000 of the population at risk.[1]

According to data from the routine health information system (DHIS2), 37 percent of outpatient consultations and 33 percent of deaths at health facilities in 2021 were because of malaria.

Malaria prevalence in children aged five years and under, who continue to be one of the most vulnerable groups, decreased from 47 percent in 2022 to 19 percent in 2021. The proportion of households with at least one ITN increased from 50 percent in 2006 to 91 percent in 2021, according to the 2021 Malaria Indicator Survey.

Mali continues to report a high proportion of severe malaria cases in comparison with neighboring countries (30 percent of malaria cases versus less than 10 percent), resulting in significant overuse of injectable drugs. Likely causes include provider preference for a fast-acting treatment, patient perceptions that injections are more effective than oral medications, lack of sufficient knowledge by health workers of differential diagnosis of uncomplicated and severe malaria cases, and the financial benefit from the sale of medicines for the facility treating severe cases (for children over five and adults).

The impact of malaria on children under five years of age in Mali is high. Mali has the 2nd highest level of severe anaemia among children under five years of age.[1] Over 40% of children who reported having a fever were not brought for care and less than 30% of the children brought for care were tested for malaria.[1] To reduce the burden of malaria in the country, the High Burden, High Impact approach was introduced in November 2019.[1]

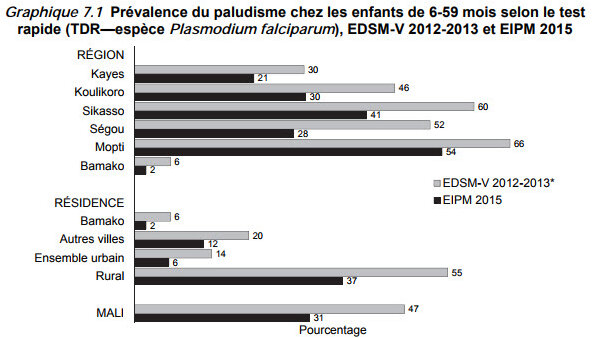

Malaria prevalence varies across regions, from a minimum of 1% in Bamako to a maximum of 30% in Sikasso region. The disease prevalence among children under five years of age was 19% in 2018.

Malaria is endemic to the central and southern regions, where about 90 percent of Mali’s population lives, and it is epidemic in the north due to the limited viability of Anopheles species in the desert climate.[2]

Anopheles gambiae s.l. is the primary malaria vector in Mali, representing 98 percent of Anopheles collected at all sites in 2021. Other species recorded include An. pharoensis, An. Rufipes, and An. funestus s.l. [2]

The country therefore has three malaria zones:

Stable malaria zones: In this zone, the disease is transmitted throughout the year, with some seasonal variations. This transmission type impacts the Guinean and Sudanese zones as well as the dams and inner Niger Delta areas.

Unstable malaria zones: These areas have intermittent transmission of malaria (mainly the Sahelian-Saharan zone) and are impacted by epidemics; local inhabitants are therefore not sufficiently immune to malaria.[4]

Sporadic malaria zones: This is typical of the Saharan zone and the population has no immunity against malaria with all age groups being exposed to severe and complicated malaria infections.[4]

The country has introduced several policies in support of pregnant women and children.[3] These include:

- free health care for children under 5 and pregnant women in 2017

- heavily subsidised care for the rest of the population

Key populations that may not have access to care include the destitute, internally displaced, refugees, repatriated and populations which have limited geographical access to health centres (over 5km), immigrants and nomads.[4]

Mali continues to have high access to (90% in 2018) and high use (79% in 2018) of insecticide-treated mosquito net (ITNs). The proportion of pregnant women (84% in 2018) and children under 5 years of age (79% in 2018) who sleep under nets also remains high. The country intends to reach universal coverage of bed net distribution by 2022.[3]

Case management

Confirmed cases of severe malaria are treated with injectable artemisinin derivatives (artesunate or artemether) or quinine. Free injectable artesunate-based kits are made available to health facilities for children under five years of age and pregnant women. Treatment of confirmed severe malaria in pregnant women is with injectable artesunate as the first-line, injectable artemether as the second-line, and injectable quinine as the third-line.

Approximately one-quarter of all malaria cases reported each year in children are classified as severe. The proportion of all cases reported as severe increased between 2017 and 2020 in both children and in persons five years of age and older. It is possible that clinicians are reporting uncomplicated cases as severe cases to justify treatment with injectable antimalarials. The Global Fund is currently planning an assessment of malaria surveillance that will also look at the misclassification of severe malaria cases.[2]

For 2021–2023, the overall need of artesunate injection is estimated at about 14.5 million vials. However, this is based on an estimated 15% to 18% of all malaria cases being classified as severe (which may be an overestimate).[2]

Malaria in pregnancy

Mali's National Reproductive Health Policy was updated in 2020, and the country adopted the WHO antenatal care model that comprises at least eight contacts between a pregnant woman and the healthcare system. IPTp is the main strategy for the prevention of malaria in pregnant women, and the policy states that pregnant women should receive at least three doses of IPTp. The first dose should be given during the 13th week of pregnancy and subsequent doses should be given at monthly intervals after that. The Government of Mali is looking at expanding the community distribution of IPTp, focusing on districts with high malaria burden and very low IPTp3 uptake.[2]

In 2018, although the majority (80%) of pregnant women attend at least one antenatal care visit, only 37% of women living in rural areas attended the recommended four visits, in contrast to 67% of women living in urban areas (Demographic and Health Survey 2018). Despite this, intermittent preventive treatment for pregnant women (IPTp) has increased over the last few years.

The proportion of pregnant women who received three or more doses of IPTp has increased from 28 percent in 2018 to 35 percent in 2021. Care-seeking for children with fever also continues to improve from 56 percent in 2006 to 60 percent in 2021, as well as malaria testing, which increased from 14 percent in 2015 to 24 percent in 2021.

Seasonal malaria chemoprevention

Seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) began in Mali in 2012. By 2018, SMC covered children less than 5 years old nationally and, in 2017–18, it was piloted for children 5–10 years old in the Kita District. The National Malaria Control Programme would like to expand to all children 5 to 10 years of age in higher-risk districts; limited resources are currently precluding this expansion.[2]

In the programme, all eligible children with fever were tested for malaria before receiving SMC. If the malaria test were positive, then the child is treated with an artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT). Children who are not severely malnourished receive the standard malaria preventative treatment of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine + amodiaquine (SPAQ). Children diagnosed with severe malnutrition do not receive SPAQ and are referred to health facilities for appropriate case management.[2] Pregnant women are also screened for fever during SMC campaigns, and those who with fever are referred for care.

The NMCP’s objective is to provide seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) in districts with high seasonal malaria transmission and reach 90 percent of children in eligible age groups during each cycle of SMC.

Although community buy-in for SMC in Mali is good, there are challenges with compliance with the last two doses of medication (day 2 and 3), potentially due to administration agents not advocating for the importance of completing the dosage and a lack of understanding on the part of parents/caregivers. Another reason is that parents or caregivers forget or lose the SMC drugs.

Severe malaria policy and practice

| Recommendation | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Strong | IV artesunate |

| Strong | IM artesunate |

| Alternative | IM artemether |

| Alternative | IV quinine |

| Alternative | IM quinine |

| Recommendation | Pre-referral |

|---|---|

| Strong | Rectal artesunate |

| Alternative | IM artesunate |

| Alternative | IM artemether |

| Alternative | IM quinine |

| Recommendation | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Strong | Inj artesunate |

| Alternative | IM artemether |

| Alternative | Inj quinine |

Market information